Piolets d'Or Announces the "Significant Ascents" of 2023

This list of 68 climbs is effectively a "long list" used to select nominees of the prestigious alpine award.

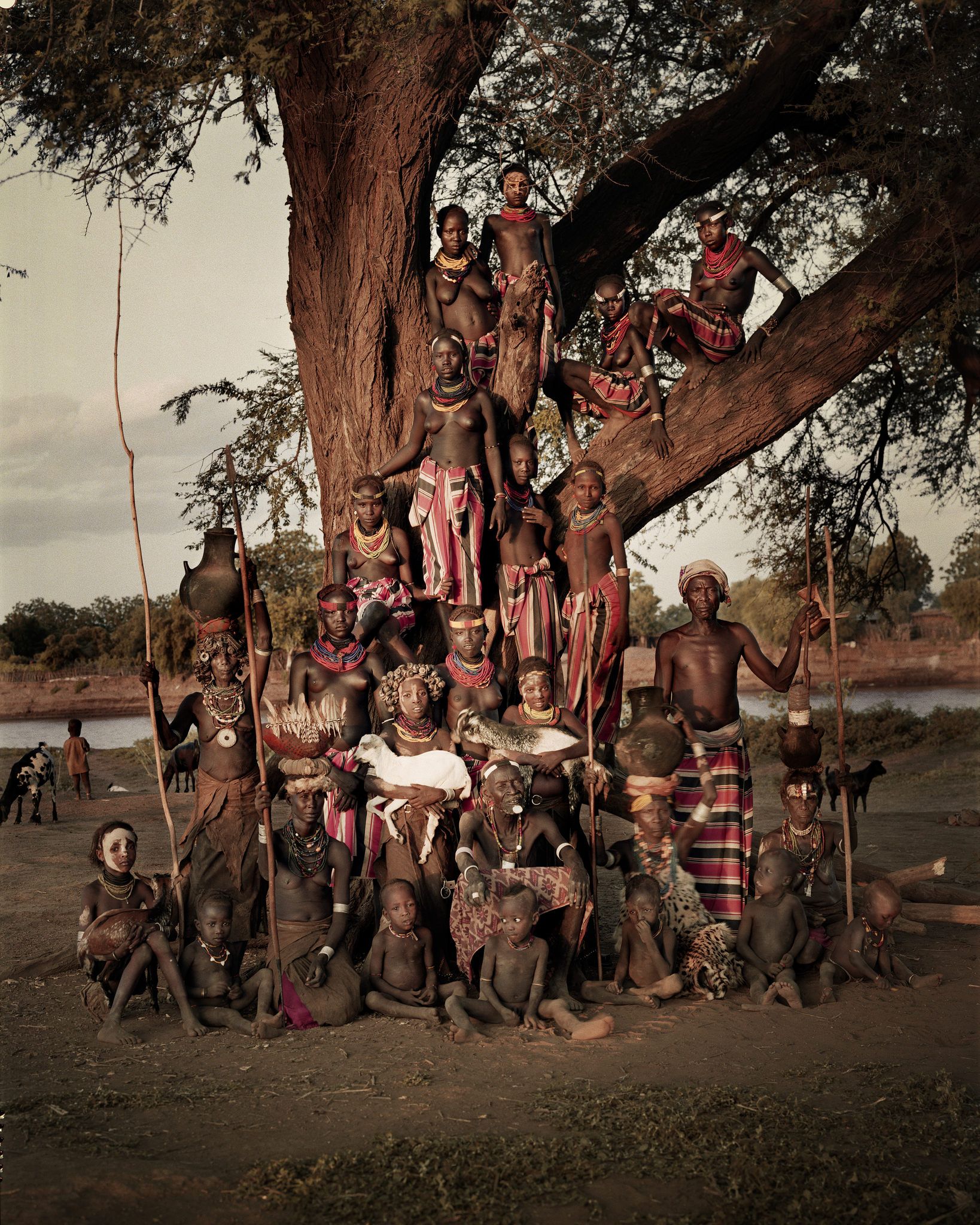

In a deeply personal journey, professional photographer Jimmy Nelson inspires future generations to honor indigenous tribes who live in the planet's furthest extremes.

To view a Jimmy Nelson photograph is to believe in wizardry. Nelson must have sold his soul to become a sorcerer of light and shadow, a summoner of fog and mist. A tribe elder stares resolutely under a hat woven from human hair. A four-year-old girl stands still while a slow shutter speed captures her radiating pride. Reds saturate through the page like bloodstains. The blackest shades drip like wet tar. These snapshots into resilient lifestyles battered by time truly resonate on a global scale.

Nelson’s lens is a small window into the world of indigenous tribes who could disappear tomorrow if our globalized society continues in its failure to appreciate them. And with them lies invaluable knowledge of how humanity can exist on this planet in a sustainable way. Nelson’s photos are more than pictures, they are heritage. In seeking out indigenous cultures in the only remote landscapes that are left for them to exist, Nelson’s innate curiosity for “the other'' holds up a mirror for the rest of us human beings living in the modern world. [Listen to Nelson's podcast episode on Spotify or Apple.]

“The curiosity I have for the other is perhaps becoming a small mirror for the world, this fascination for indigenous people presented in such a proud, dignified, beautiful way is becoming a mirror for us as human beings in the developed world.”

Learn more about Nelson's latest book Homage to Humanity.

In a way, these settings are manicured versions of reality. The mise-en-scène is not what you would see if you fell out of the sky and landed on the same tribal village. The subjects often wear ceremonial headdresses that are reserved only for special occasions, not daily use. Although, taking a quick glance in the background might reveal others dressed head to toe in the traditional garments they typically wear, while a child or two runs past in a t-shirt. [There’s an app feature built into Nelson’s book that brings up footage of Nelson shooting on location.]

For Nelson, photography is a process that taxes his entire being. Reserved and restrained, he’ll often observe an indigenous community for weeks before dusting off his camera. Very often, these communities are so remote that they have never seen a white person and they’ve never been visited by car. Despite stark cultural barriers, Nelson builds rapport and trust by making himself vulnerable, even at the risk of mortifying embarrassment.

“The further I go on this journey, the more I invest, the more vulnerable I become and the more I submit to the process, the more true I am becoming as me.”

It’s never a guarantee, but when weeks of physical discomfort and emotional investment come down to one moment where everything aligns for that one shot that will stand the test of time, it looks and feels like magic.

Nelson doesn’t see himself as a photographer or even an artist. He’s a searcher. He submits himself to a process with no aspirations to reach the endpoint. The process is his way of being. Nelson’s custom camera is just a medium to better understand his identity, which was completely destroyed as a young boy.

Nelson’s childhood see-sawed between manic extremes of freedom and terror, which imposed a life-long journey on him to reconnect his soul with his body.

During his formative years, Nelson lived the life of a third culture kid, a vagrant expat traveling throughout Africa, Asia, and South America with his family. His childhood reads straight out of Rudyard Kipling’s The Jungle Book - a wild, school-free existence.

“Every day was a discovery and exploration, I hadn’t been to school in seven years, I couldn’t read, couldn’t write but I could climb every tree on the planet and I knew the name of every different snake.”

Nelson’s father was a geologist who dedicated his waking life to studying rocks deeply, perhaps to discover insights about himself, and little else. His life’s obsession was the Antarctic, living with husky dogs in a tent, and his method was his hammer, cracking away at the earth to uncover his soul. Nelson’s father later committed suicide because he could never recover that soul, so to speak, after aiding the oil and gas industry at the detriment to the planet that he loved.

“My dad was an autistic. He was a professor who spoke about 15 languages although he couldn't look at you as a human being…one of these overly-applied intellectual brains but can’t apply himself as a basic human being.”

At the age of 7, Nelson was ripped away from his nomadic existence and sent to Catholic-Jesuit boarding school in the UK, where he suffered extreme sexual abuse.

“I arrived, putting it bluntly, as fresh meat.”

All at once, Nelson’s trauma caused him to lose innate trust in his environment.

“One minute you trust the world and everybody and everything in it, then you are taken and put in an environment that is called safe, but is a complete bipolar of the wildness that you just left. I was planted in an environment that was meant to be safe but instead, the opposite happened - I was destroyed, and that began this journey of ‘Who the hell am I? How the hell do I feel? How the hell do I not want to feel? What do I not want to remember, and what do I perhaps want to reconnect to?”

In a dark way, Nelson views the scars of his childhood as a blessing, because they imposed a journey on him to reconnect his soul with his body that was disconnected at the age of 7, spending the rest of his life trying to realign it, through incessant curiosity. Nelson continually surrenders to the process of self-reflection through his visual meditation of the other in these remote, tribal experiences.

“Sometimes scars help because you never forget them because you look at them every day.”

For someone who travels so far out that he is on the verge of death on occasion, Nelson’s work, and the process that defines it, has achieved remarkable longevity.

“I’m not afraid to die on these field trips. I’m not dismayed by the risk. The disease of the modern world is the compartmentalization of death. It keeps people from living in the present moment. If it ends tomorrow, what I am doing today is exactly what I wanted to do.”

At the time of this interview, Nelson had just returned from another one of those islands that you wouldn’t mind being abandoned on - Lamu island off the coast of Kenya - where he went sailing with Somali fishermen, something he was told could not be done.

Each time Nelson enters a period in life where he hits a wall and feels the need to disappear again, he’s off to the depths of winter in Mongolia, or a remote community in the jungles of Brazil, or an isolated volcanic archipelago somewhere in the Pacific.

“I'm at my happiest at minus 50 degrees on a mountain in Mongolia with a Cossack but at the same time in a remote valley I’ve never been to in Papua New Guinea.”

When he’s voluntarily grafted into a nomadic reindeer herd crossing far stretches of central Mongolia, the language barriers make it impossible to have a profound conversation or explain personal principles. There’s no other choice than to acquiesce to the role of observer.

Nelson learned his lesson of how to avoid cultural taboos the hard way, by becoming a laughingstock to his nomadic hosts, which turned out to be a fantastic way to to break down cultural barriers and engender empathy. After finally caving in to their nightly offering of their “jet fuel alcohol that you could put in a Mig and it would reach the stratosphere,” Nelson’s drunken attempt to relieve himself in the middle of the night resulted in chaos, with a crashed sleeping and overly rambunctious reindeer lapping at his pants. [Listen to the full story.]

“It was the first time we made eye contact. It was the first time they touched me. Looking back, because I had to let go of absolutely everything, because I became the baboon, the fool, I was vulnerable. As a result of that, they were empowered to laugh at me, to mock me, and subsequently guide me and help me in my cause to communicate with them. Prior to that I had held myself on a pedestal, not truly daring to be open, to be naked, to be vulnerable, but by inadvertently making a childish mistake, it was a way of breaking down barriers.”

When we inevitably blow ourselves to smithereens, our civilization as we know it will end, but indigenous tribes will persist because they know how to survive off the land. Indigenous tribes are the guardians of lands that are rich in minerals and they are also the preservers of ancient knowledge of how humans can live in alignment with the Earth. Although these peoples are often disrespected and marginalized in today’s world, the Jimmy Nelson Foundation seeks to reeducate our youth to see the power and wisdom of the indigenous communities.

“In the developing world, people wake up in the morning and think, how can I serve Mother Earth, but in the developed world, it’s the other way around, Mother Earth is in service to us.”

Nelson urges indigenous communities to hold on to their sustainable traditions despite the temptations of smartphone conveniences - because not only do they need it, but the rest of humanity needs them to preserve this knowledge too.

“Our world is phenomenal. Look at how we’re communicating today! There are technologies that in our wildest imagination we wouldn’t have believed would have existed twenty years ago. But it’s how we use that technology and apply that to deep, deep, deep human wisdom, and that’s what the indigenous communities have.”

Nelson's efforts to fastback awareness in the younger generations will hopefully generate enough support to find creative ways to apply ancient knowledge into the future of our globalized society.

Nelson’s photos are just the most visible sign of his efforts to help raise support and awareness for indigenous peoples of the world and to figure out how we can better live with one another.

“This is the challenge, how can we, with everything we do, connect to a new generation to enable them to see the world with love and trust, to not be afraid, and to find a way to be inspired by human beings, that no matter how they look or how they dress or what they believe in, stand and live and connect with the natural world in the most beautiful, humble way imaginable.”

By educating our youth, we can begin to re-understand the planet’s resources and make better choices that are in alignment with a sustainable relationship with nature.

Nelson’s revered photography career has placed him on a quest that he hopes will never succeed - to make a transcendent image that goes beyond photography.

“I am aspiring to have one definitive picture. To have one picture that will stand the test of time or be a legacy so that when I’m long gone, like a piece of sand blowing in the breeze, there will be one picture that represents the aligning my story and my search with a piece of art that will resonate.”

[gallery type="slideshow" size="full" columns="1" link="none" ids="19276,19279,19298,19297,19292,19291,19300,19299,19303,19302,19301,19296,19295,19294,19293,19290,19289,19288,19287,19286,19285,19284,19275,19283,19282,19281,19280,19278,19277,19274"]

Nelson is drawn to the tangibility of analog cameras because of, not despite of the fact that so much more work must go into capturing that perfect moment. He departed to Kenya with only ten sheets of film on him, trusting that he would have the patience to narrow the experience to a very fine, selected moment.

“I’m so obsessed now that I’ve found a young man in Italy in Maranello where they build Ferraris who builds me eight by ten cameras out of titanium.”

Nelson embraces his Sisyphian struggle to repeat and refine his process of making the perfect representative photo to last forever.

“I dare say it is not possible and will never be possible but the process and the search to try to realize it is the thrill. And to accept that it’s probably an impossibility is also beautiful but to indulge in the process is heaven on earth.”

Nelson knows when that perfect moment arrives - when the image in his analog viewfinder matches the emotion he is seeking.

“It's the process, the hunt, the search, the seduction, the failure, the investment, the tears, the peeing on tents, the cold, the pain, the laughter, it's the love. And if you’ve submitted to the emotional journey and you’re out there in your rawest form, then you might get lucky enough to make your picture.”

You can order your copy of Homage to Humanity, with over 500 pages of photos, here.

In this episode of The Outdoor Journal Podcast, Nelson discusses the source of his unlimited fascination with indigenous tribes, how he ingratiates himself into strange, yet more harmonious cultures, and how his obsession with photography reveals profound insights about himself.

Read more about Jimmy Nelson in Three Minutes of Bliss.

Follow Jimmy Nelson on social media:

Facebook: @jimmy.nelson.official

Instagram: @jimmy.nelson.official

2nd best newsletter in the universe