Piolets d'Or Announces the "Significant Ascents" of 2023

This list of 68 climbs is effectively a "long list" used to select nominees of the prestigious alpine award.

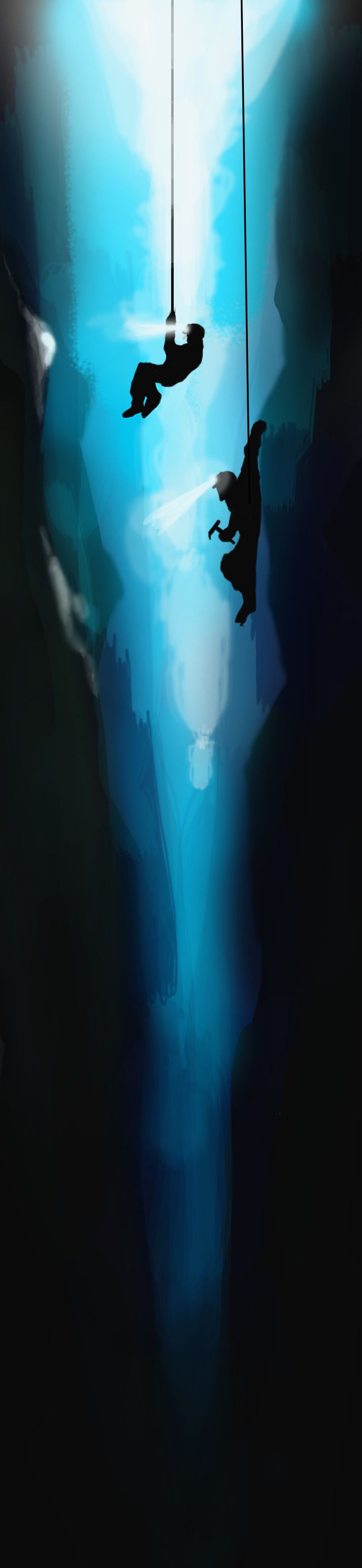

Two men drive a jeep off a glacier and into a crevasse in Iceland. A US Air Force PJ recounts his role in a civilian rescue mission while stationed at a naval base in the North Atlantic.

This story originally featured in a print issue of the Outdoor Journal. You can subscribe here.

November, 2006. The call came in as our team was having dinner at our base in Keflavik, Iceland. A civilian jeep had fallen into a crevasse on the massive Hofsjokull Glacier. The jeep was wedged 80 feet down, with unknown passengers trapped inside. Accessing the jeep and saving these people would be complex and dangerous, so local authorities had called in the American military’s elite rescue team.

As a Pararescueman (or PJ) I worked on a team with some of the most elite soldiers in the U.S. military. PJs are highly specialized personnel, trained to conduct high-risk combat and civilian rescue operations at a moment’s notice, anywhere in the world. Unlike other special forces - Navy SEALs and Army Green Berets - who are trained to hunt and take life, the PJ’s primary mission is to save life: we resort to lethal force only when necessary to protect our patient. I was stationed at Keflavik, from where we conducted military rescue operations but also extended our services to the local Icelandic population when needed.

We rushed to the staging area where our equipment was waiting for us, along with a fleet of HH-60 Pave Hawk helicopters. I could feel the adrenaline surging in my blood, my heart rate quickening.

The key to successful execution of high-pressure rescue is to remain calm. No matter how unlikely success may appear, one must be confident that he or she has the skills to overcome any situation. One must improvise, based on instinct and years of training, often thinking well outside the box. Since the very first days of our training, we had been taught to adapt, overcome and complete the mission at any cost.

The U.S. Navy base at Keflavik was established during World War II to defend Iceland and secure northern Atlantic air routes, and remains in operation 60 years later. The PJs stationed at Keflavik were on hand primarily to support F-16 fighter jets maintaining patrols over the icy northern Atlantic Ocean. Any time an F-16 is in flight, two assigned PJs are on alert and ready to immediately respond to any incident. Additional PJs are on alert 24 hours a day to respond to civilian rescues for the country of Iceland, a service provided to extend goodwill to our hosts. When PJs are not performing actual missions, they spend their days preparing and training, always sharpening their skills for future missions.

At my locker in the PJ building, I suited up for the mission in warm layers and Gore-Tex. I grabbed my rucksack and filled it with goggles, gloves and miscellaneous survival gear. Nearby, my teammates Alex and Matt suited up for the mission. In addition to the usual medical equipment, we loaded an extrication device (“Jaws of Life”), extensive high-angle ice-rescue gear, and a full complement of glacier camping equipment, as we had no way of knowing how long the operation would require us to be out there. We headed outside to the launch pad, where maintenance personnel were making last-second checks on our bird.

“Ready to rock and roll,” I responded.

The HH-60 Pave Hawk helicopter is the Air Force’s primary aircraft for combat and civilian search and rescue operations, a modified version of the well-known Blackhawk choppers, equipped with advanced cold-weather capability for the sub-arctic environments across the north Atlantic. In addition to rescue operations, the Pave Hawk is frequently used for humanitarian aid and disaster relief missions throughout the world and is often seen in images of U.S. military personnel providing supplies or aid to victims of natural disasters.

As the thud-thud-thud of the chopper blades slowly increased in tempo, we loaded up men and gear into the cabin and were greeted by our pilot, Captain Thomas.

“How are you guys doing back there?” Captain Thomas asked over the intercom.

“Ready to rock and roll,” I responded. As a crucial member of our team, the pilot is all business during a mission, but Captain Thomas had a style and grace far beyond most of the guys: I had noticed her long, curly chestnut hair and very fit athletic build. Being a woman in the Air Force special operations is not easy, and I saw our pilot as inspiring proof that gender differences are often irrelevant in the face of hard work, talent, and raw determination.

I had been a PJ for three years, and was working towards a promotion to team leader. On this mission, Alex was officially the team leader, responsible for important decisions and ultimately accountable for the outcome of the mission. On paper, I was still a team member, but recently I’d been assuming more of a leadership role as my confidence and experience mounted.

“PJ Team Lead, how do you want to execute this?” Captain Thomas asked over the intercom. No response. After an awkward 30 seconds of silence, I looked over at Alex and was stunned to see the uncertainty in his eyes.

Again the pilot asked, “PJ Team Lead, what is the game plan here?” Another 20 awkward seconds went by, as time seemed to stand still. Meanwhile Alex, a bona fide bad-ass and highly seasoned PJ, was simply freezing up. At the same time, I felt comfortable and in my element, having spent years in the mountains, navigating crevasses and climbing mountain faces and frozen waterfalls as a recreational alpinist, and high-angle rescue was one of my strongest skills in the quiver of PJ specialties.

I keyed the microphone and responded to Captain Thomas. “Let’s do a flyover of the scene to take a look, then try to find a safe place to land. From there we can move as a rope team to the crevasse or perhaps you can drop us in on the hoist.”

“Roger that,” Captain Thomas responded, her voice focused and alert.

I looked at Alex, knowing now was my time to assume the team lead role. I felt confident and capable, and unlike Alex I had been raised in the snow. Having climbed mountains for most of my life, I understood glaciers and crevasses, and although I fully recognised the dangers present in the unstable medium, and the complexities involved in a patient extrication from 80 feet deep in the ice, I felt comfortable in the environment and ready to use my abilities. If there was ever a mission built for me, this was it.

It is not uncommon for candidates to lose consciousness underwater.

As the Pave Hawk carried us toward the Hofsjokull Glacier, I thought back to my PJ training. Conducted under the cruel sun of the hot Texas desert, some call the intense and brutal indoctrination course of the PJs the most difficult selection process in the U.S. military. Ten weeks of total hell, followed by an 18-month training pipeline during which 90 percent of candidates are eliminated. Beginning each day at 4:30 am, mandatory training includes running, calisthenics, push-ups, sit ups, all in the heat, numbering in the thousands per day. But this portion of training is actually the easy part: the real hell starts in the indoor pool.

Each candidate sits at the edge of the pool, with his diving mask, fins, snorkel, weight belt and booties perfectly aligned behind him. As the instructors approach the 100 aspiring PJs, a loud guttural war cry fills the indoor facility with bone-chilling intensity. All are aware that the pool is where most PJ hopes and dreams will be shattered. My second week in the program, I decided I was willing to die trying to make the cut.

“Enter the water!” the instructor yells. In perfect succession, the first row of candidates enters the water and performs a 25-meter underwater swim. Throughout each 4-hour pool session, instructions must be executed perfectly. Instructors pay ruthless attention to every candidate’s every move, issuing swift and severe consequence, usually involving additional underwater suffering, to the slightest mistake. It is not uncommon for candidates to lose consciousness underwater. Fortunately, I had just finished a career as a college distance runner, so my body was familiar with operating on depleted oxygen. I was also very determined not to get washed out. This determination paid off and I was eventually successful in making the cut to become a special forces Pararescueman.

Five years later, and now en-route to the Hofsjokull Glacier, I was thankful that the instructors had not been easy on me. They taught me valuable lessons and to pay close attention to detail.

In this business, the smallest mistake can get you killed.

Upon arrival at the scene we found a gently rolling landscape of white snow and ice littered with crevasses. I spotted a large crevasse with jeep tracks straddling the slit, ending at a broken hole where an ice bridge has collapsed. Three people were near the crevasse, aware of the situation but unable to help.

Over the intercom, I directed Captain Thomas to land about 600 yards from the crevasse, in a flat area where the jeeps had driven and their tracks indicated surface stability. We exited the aircraft on a roped belay while probing for crevasses. After we had deemed the landing area free of crevasses, we unloaded all our gear from the Pave Hawk and the bird took off. We immediately loaded up our large packs and moved to the accident scene, still roped up to protect against falls into any hidden crevasses.

We greeted the three Icelandic men standing at the scene, then probed the surrounding area to confirm that we could unrope and move about the area safely. The men were local firefighters and had arrived on scene minutes earlier via glacier jeep.

I asked the firemen about the status of the passengers in the jeep. They indicated that one man was dead, on the upright side of the jeep, with one survivor trapped on the bottom side. They didn’t know the survivor’s condition other than that he was injured, cold and very uncomfortable, as the jeep had been severely crushed in the fall. The roof of the jeep was compressed down below its windows, and the patient was not in a good situation. In addition, the instability of a vehicle wedged into the ice presented serious danger to rescuers at the vehicle.

Alex allowed me to take control of the mission, even though he was the team leader on paper. I directed the team to set up some ice anchors and send rappel ropes down into the crevasse. Matt and Alex then rappelled down into the darkness, along with two of the Icelandic firemen. Upon arrival at the jeep they placed several ice screws into the walls, creating a safe anchor to protect them from slipping off the side of the vehicle into the abyss and also provide a safety net in the event the jeep should shift and suddenly fall further into the darkness.

The temperature was 38 degrees Fahrenheit and dropping fast as the sun descended toward the horizon. Working quickly, Matt called for the extrication equipment and indicated their plan: “We are going to remove the driver’s-side door to gain access to the deceased, and hopefully to the survivor.”

“Roger that,” I respond, and prepare to send down our Jaws of Life. As we work, several glacier jeeps approach from different directions; word of the accident has gotten out and it appears that every rescue team in Iceland is keen to help.

The first jeep pulled up and a tall, solidly-built man got out and introduced himself as Bjorg. As I briefed him on the situation, I mentioned the trouble we anticipated with our small Jaws of Life trying to cut open the crushed jeep. Bjorg explained that he had a more powerful Jaws of Life, currently en route via truck from the other side of the island—hours away. With the impending darkness and dropping temperature, I knew time was of the essence. I realised we may be able to speed up the extrication process by sending the Pave Hawk to intercept the Jaws, and immediately directed Captain Thomas to rendezvous with the vehicle carrying them across the island. She fired up the helicopter and, with GPS coordinates for a rendezvous point established, headed north to fetch the crucial tool.

More jeeps continued to arrive, all carrying well-intentioned volunteers or professional rescue teams. Bjorg stated that he would be the Icelandic in charge and that he and I would work together to get this done safe and efficiently. A few moments later an independent rescue team dressed in matching red uniforms arrived and started questioning everything: our equipment, our plan, our leadership. With no time to be distracted, I calmly asked Bjorg to tell the man to step down and that everything was under control. He sternly told the man and his team to step back, and we were able to proceed unhindered.

Just then I heard the dull thud of the helicopter returning. “DeTray,” Caption Thomas asked over the radio, “where do you want these Jaws put down?”

“Lower them right down on top of us,” I responded.

“Roger that,” and with a precision hover she had the flight engineer lower the package. “DeTray, how much more time do you need?”

I indicated we weren't sure but would probably need several hours. She needed to return to base to refuel, and promised to be back soon. “Roger that, see you in a few hours,” I responded. The bird took flight once again and disappeared into the distance.

With the help of the Icelanders I lowered the more powerful Jaws of Life down to our crew in the crevasse. Removing the driver’s door, which had been violently crushed by the fall, proved very difficult, but eventually Alex called for a litter to be sent down. Soon the body of the deceased was loaded and hoisted to the surface, where it was placed in a body bag.

Next, Matt’s voice came over the radio: “Detray, I have some bad news. We were hoping to be able to get to the trapped man through the driver’s side, but the roof has collapsed down to the centre console. It looks like we will need to rappel down under the jeep and attempt to remove the door from the underside.”

My head swirled with the infinite number of things that could go wrong with this plan. I trusted my teammates’ judgment and assessment of the situation, but I also understood the risks of sending men under the jeep. If the jeep were to shift position, it could fall and crush my men. As acting commander, I would be morally responsible for any injury to my team. I took a deep breath and told Matt to do what he felt was the right course of action. “I know you want to save him, Matt,” I radioed, “but please be careful down there.”

The men descended below the jeep and began to work on the lower door. Light from their powerful headlamps and the roar of the Jaws of Life drifted up to the surface, eerily echoing off the icy walls. Time slowed to a standstill, and I could feel the pressure of the situation while waiting. Matt had just been married and I suddenly felt heightened awareness that I was responsible for his safety. I sure didn’t want to have to give his new wife any bad news.

The evening sun finally set and darkness settled over the scene. Alex radioed up to me, requesting the litter and stating their plan to remove the lower door and guide the patient into the litter. I reminded the guys to be sure the patient was secured with a rope to prevent him tumbling deeper into the crevasse.

The plan went off perfectly. The door of the jeep was removed and the patient was loaded into the litter and secured. Alex radioed up requesting a slow raise of the patient, and our crew on the surface brought him up. Just as we pulled the patient over the lip of the crevasse, I heard the sound of the Pave Hawk roaring back onto the scene, and at that very moment the Aurora Borealis broke into a beautiful display of blues, greens and reds dancing in the arctic sky.

“Pilot, we have just extracted the survivor and he is stable and ready for transport. Request hoist pick up.”

After an hour flying through the arctic darkness, we could see the bright lights of Iceland’s capital Reykjavik and soon Captain Thomas landed on the helicopter pad of a modern medical facility.

We had pulled off a difficult mission, where success was uncertain. Despite difficult conditions and high risk, we were able to extricate and transport our patient, saving his life, without incurring any injuries to the rescuers.

Illustrations by Rimo Dey

Text by: Skiy Detray

2nd best newsletter in the universe