Piolets d'Or Announces the "Significant Ascents" of 2023

This list of 68 climbs is effectively a "long list" used to select nominees of the prestigious alpine award.

Few in the passionate throng who anticipate the annual Ironman race realize how close the original idea for the race was to being left for dead. This is the story of Ironman’s unlikely genesis.

This story was first published in print, in the Fall issue 2015 of the Outdoor Journal.

There are, at the time of writing, 35 official Ironman triathlons that take place around the world. From Brazil to Australia to Malaysia to Japan to New Zealand to the Ironman’s birthplace in Hawaii, each race starts with a 2.4-mile swim, then follows with a 112-mile bike and finishes with a marathon. Despite the ridiculous physical demands and discomfort required to finish an Ironman (isn’t running a 26.2 miles long enough?), participation in a significant number of these races sells out every year.

It’s difficult to believe that the now-iconic endurance series of races began simply, with a bunch of friends drinking beer and bantering about endurance sports the way a football fan might talk about their favorite team.

There was no prize money and no one was even sure if the thing could be finished or how long it would take to finish.

In 1977, on the Hawaiian Island of Oahu, at an awards banquet following an around-the-island running relay, the spirited debate question was which kind of athlete is the best endurance athlete: the swimmer, the runner or the cyclist? At the time, Belgian Eddie Merckx was dominating cycling, including the Tour de France, and John Collins, a U.S. Navy Commander stationed on Oahu with his wife, Judy Collins, reasoned that a cyclist like Merckx, who had recorded epic oxygen-uptake capacities in an exercise lab, and seemingly mastered the unforgiving nature of multi-stage cycling, made a pretty good argument that cyclists were the best. The discussion spiralled upward, perhaps due to endorphins and ice-cold refreshments, and the concept of piecing together the Honolulu Marathon, the Waikiki Rough-water swim and an around the island bike ride took shape. Impassioned with the thought of an epic triathlon, Collins took to the stage of the awards ceremony during the band’s intermission and threw down the gauntlet—the race would be called the Ironman, and whoever finished first would be identified as the fittest.

But as such things go, the wild idea was just that – wild -- and carrying it out was easier said than done. But Collins continued to mull it over, and a few of the local endurance crazies helped keep it alive by bugging him about it. As fate would have it, in 1978, it was John and his wife Judy’s turn to stage a race for the local running community. They decided to go ahead with the Ironman idea that was born a year earlier and nearly forgotten. Collins wrote the copy for the flyer that was printed up and posted around town. It read: “Swim 2.4 miles! Bike 112 miles! Run 26.2 miles! Brag for the rest of your life!”There was no prize money and no one was even sure if the thing could be finished or how long it would take to finish.

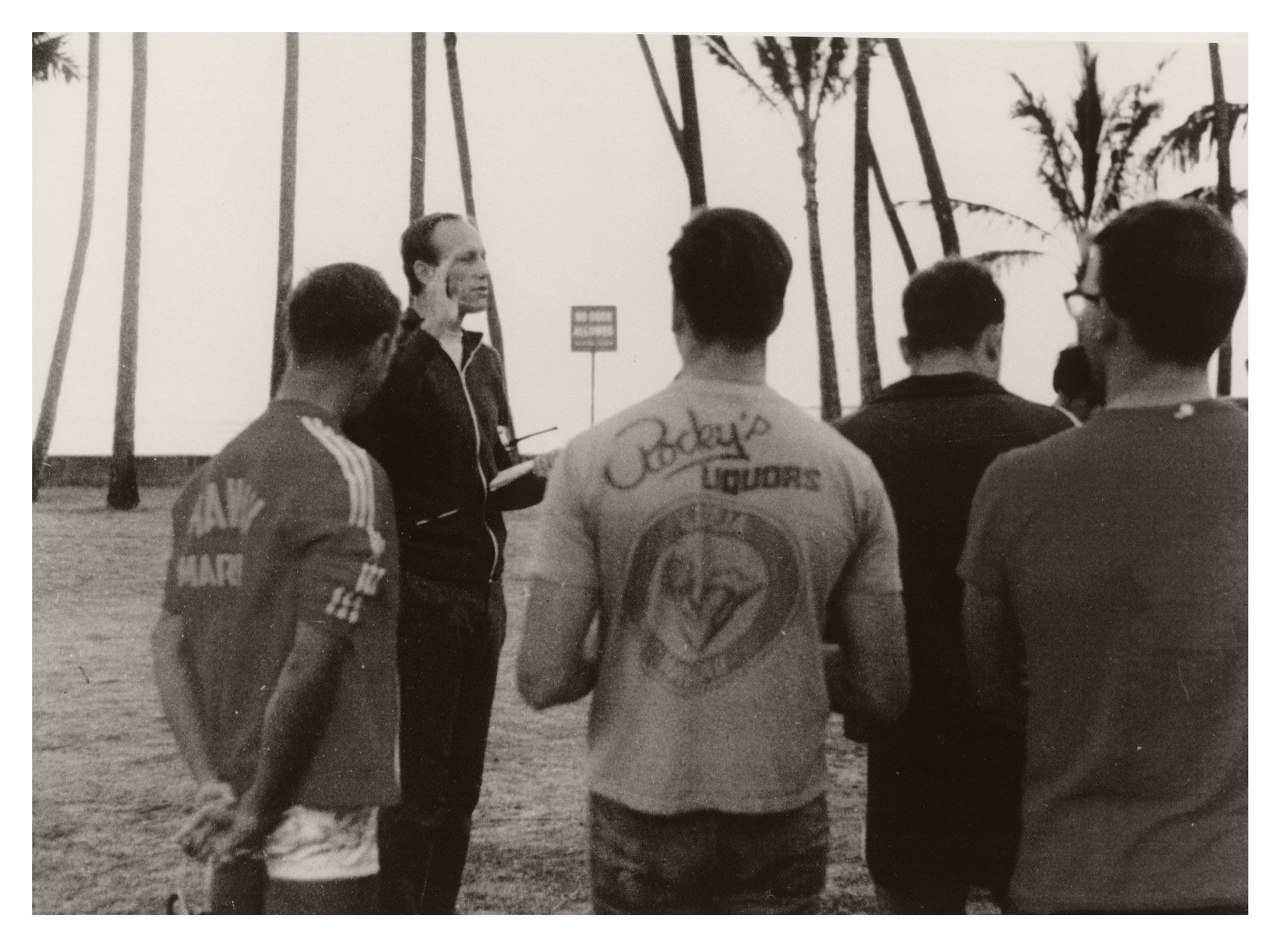

A paltry 18 contestants showed up with their swimming suits, bikes and running shoes on a Waikiki beach on the Hawaii Island of Oahu. There were no women racers the first year. Each of the athletes was required to have a support crew throughout the race, including a kayaker to make sure they finished the swim safely. John Collins not only acted as race director, but he entered and joined the others on the starting line.

The first Ironman turned into a battle between Gordon Haller, 28, a former communications specialist for the U.S. Navy, and John Dunbar, 25, a former Navy SEAL. Haller and Dunbar beat on each other throughout the day, with Dunbar taking over the lead several times during the day but consistently running into problems like dehydration. Haller’s metronome-like pressure would ultimately lead to Dunbar’s ruin. Dunbar, who had trouble getting all of his supplies together the night before the race, ran out of water during the marathon and started hallucinating. He drank two beers 10 miles from the finish, making things palpably worse. Haller eventually won in a time of 11 hours and 37 minutes.

With the advantage of nearly four decades of hindsight, it would seem that Haller was the perfect answer to the riddle of ‘who is the best endurance athlete, the swimmer, the cyclist of the runner?’ He was all the above. He was also an exercise junkie who traded in his job driving a taxicab for a roof repair job so he could exercise more. In the classic Sports Illustrated article that cast the first media light on the Ironman, published in 1979, Haller was described as being so obsessive-compulsive about working out—running, swimming, biking, lifting weights and more—that he nearly killed himself with a slew of immune system disorders:

Haller was working out three times a day, had two girlfriends, was staying up all night to study for exams and was preparing to run the quarter-mile and half-mile in a local track meet. In quick succession he had mononucleosis, strep throat, hepatitis, dysentery, tonsillitis and trench mouth. His legs became paralyzed. "Then I really got sick," he said His convulsions were so severe that he suffered a double hernia. "It was a good time to lay back and reflect on life—what was left of it." Haller lost 28 pounds in one week. "At the end of the week, Neil Armstrong walked on the moon and I ate my first meal," he recalled.

That was a fitting description of the first winner of the “Hole-in-the-Head” trophy that Collins had cobbled together. Another interesting quality about Haller that resonated through Ironman history was that he was a physicist. In surveys gathered at the Hawaii Ironman in the past decade, one of the most common professions is engineering. Haller was the prototype for the generations of age-groupers that would ultimately rain down on the courses of Ironman triathlons everywhere: He was smart, methodical and a little weird. And if you gave him 24 hours with nothing else to do, he’d pack in as much training as physically possible.

Haller experimented heavily with super clean diets. This was new. Runners at the time were known to eat whatever they wanted and as much as they wanted. But to this day, like Haller, triathletes are always looking out for an additional edge in nutrition and technology, such as the Zone Diet or a breakthrough design in carbon-fiber wheels. Hall was the pioneer.

The challenge of the Ironman proved too much to resist.

The Sports Illustrated article reported on the second edition of the Ironman, when 28 people were expected to show but only 15 started. The article acted like a homing beacon. The mailbox at the Collins household began to fill up with letters. He also received a call from ABC television, which wanted to send a Wide World of Sports crew to film the 1980 event. Collins has a deadpan sense of humor, and used it to communicate what he felt was just a raw fact when it came to a race that took some 24 hours to finish. In talking to the ABC producer, Collins said “Sure, you can come film it, but it’s about as exciting as watching the grass grow.” Yet the footage that made the airwaves continued to touch off the same nerve as the Sports Illustrated story. The challenge of the Ironman proved too much to resist.

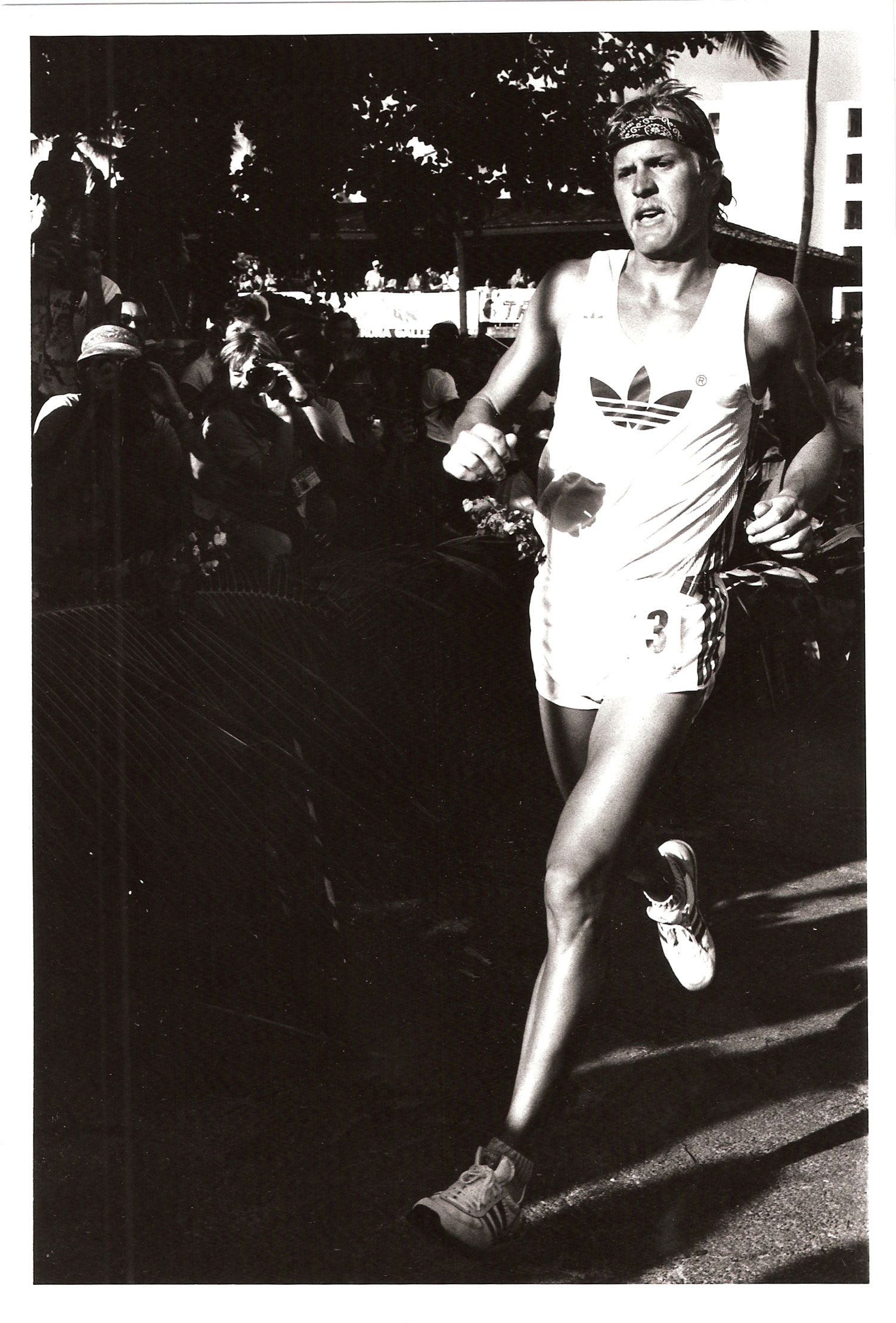

Davis, California is home to a branch of the University of California. The land surrounding agricultural epicenter is hot and windy, turning out to be perfect training setting for a star high school and university water polo player Dave Scott, who, not unlike Haller, liked to work out all the time. Scott’s arrival at the Hawaii Ironman would have profound effects on the metamorphosis of the event from a test of survival to a competitive sport. To prepare for his first race in 1980, Dave Scott went to Oahu and did the race solo, just to see if he could do it. He returned to his first Hawaii Ironman and won, smashing the 10-hour mark by more than 35 minutes. He turned the Ironman into a race out of something that was simply meant to be survived.

Dave Scott led the way for what came to be known as The Big Four: Dave Scott, Scott Tinley, Mark Allen and Scott Molina. These four triathletes were the four most dominant male triathletes in the 1980s. They had distinct personalities—Dave Scott was the lone wolf in Davis, an athletic-scientist type with an enormous appetite for hard training. Scott Tinley was the iconoclastic rebel, who began writing an opinion column for Triathlete Magazine. At first, Tinley recorded the columns on a tape recorder and sent them to the editor-in-chief, Bill Katovsky, who handed it off to an assistant editor to transcribe. Later, Tinley would handwrite the columns on a piece of paper and fax them to Triathlete Magazine. (I know this for a fact because one of my first jobs as an assistant editor there was to type of Tinley’s columns into the computer). Tinley’s brash, Steve Prefontaine-like joy for triathlons helped galvanize the sport. Scott Molina was the blue-collar working man type of athlete, ultimately winning more than 100 races in his career, and known for his work ethic and speed at the Olympic triathlon distance.

And then there was Mark Allen, a wickedly talented athlete who had grown up in Palo Alto, California, and became part of triathlon in 1982 after he watched the Hawaii Ironman on TV. For Allen, winning the Hawaii Ironman and defeating Dave Scott became a quest — one he was repeatedly denied from achieving. Throughout most of the 1980s, Allen would start off the Hawaii Ironman as a favorite but suffered one spectacular meltdown after the other, ultimately losing each time to Dave Scott. The titanic rivalry that formed brought all the more attention to a sport that just was beginning to take. The greatest Ironman took place in 1989, when Allen matched Scott stroke for stroke and stride for stride through the swim, the bike and most of the run until finally, with seven years of failure feeding into his motivation, Allen was able to put a gap on Scott and make the break for victory. Allen ran a 2:40:03 marathon split to net an 8:09:08 victory. (The 2:40:03, after 24 years, remains the fastest marathon split in Hawaii Ironman history). Allen would go on to win five more Hawaii Ironmans and by the time both Allen and Scott had retired, each had six crowns to his name.

Whereas the competitive sparks between the Big Four were responsible for inspiring a legion of hotshot athletes from around the globe to pursue triathlon, it was a slender woman named Julie Moss who has long been credited with catapulting the Ironman into being a large-scale participation sport. Although the 1978 field of athletes was devoid of women, in 1979, Lyn Lemaire, a cyclist from Boston, was the first female to participate. Thereafter, women triathletes began making up a sizable percentage of the field. In 1982, with ABC cameras following her every step, Moss was leading the women’s race when her body shut down. Both her leg muscles and inner organs began to falter, and the dramatic imagery of Moss refusing help as she was reduced to crawling her way to the finish line, in second place, somehow resonated with people from all walks of life who felt they had never really been tested the way an Ironman would test them. The Ironman went from a fringe event to a kind of Mt. Everest climb for people who had jobs and kids. It appealed to people who really wanted to find out who they were, what they were made of, and how much they could endure.

By the time the 1990s rolled along, the Ironman had changed in a way Dave Scott never expected: it went global. Triathletes from around the world began showing up, and although Mark Allen continued to defend his crown through to 1997, his battles were more and more against great athletes from other countries, including Brazil, Australia and Germany. In fact, it was a young Thomas Hellriegel, a German who was a powerhouse on the bicycle, who put Allen against the wall in 1995, building a 13-minute lead off of the bike and tempting Allen to veer off the marathon course to the comforts of his condo because the lead seemed so insurmountable. Allen dug in and steadily chipped away at Hellriegel, taking back the lead and winning what would be his final appearance in Kona.

But it was Paula Newby-Fraser, from Zimbabwe, and Erin Baker, from New Zealand, who took over the women’s race at the Hawaii Ironman in the mid-1980s and helped usher the Ironman into the international era that it now enjoys. In a rivalry that took on the same sort of traction that the Scott versus Allen rivalry had, Newby-Fraser and Baker began battling each other in the late 1980s, with Newby-Fraser going on to win 8 Hawaii Ironmans, and 24 Ironmans in all as the series began to grow. In the mid-1990s, it became hard to imagine that anyone else besides Newby-Fraser and Allen would ever win the Hawaii Ironman, unless Dave Scott came back, which he did in 1994, a year that Allen had taken off to focus on running a marathon. Scott had been away from the Ironman for five years. One American athlete, Cameron Widoff, openly scoffed at Scott’s coming back — insinuating that Scott, who turned 40 in 1994, was well over the hill.

Scott blistered past Widoff during the run, coming in second to Australian Greg Welch. In an interview afterwards, Widoff admitted how wrong he was and offered Scott a bow. Welch’s win seemed to inspire a fresh legion of top triathletes from Australia who would flow in to the sport in the late 1990s and beyond. Michellie Jones, Chris McCormack, Craig Alexander, Pete Jacobs and Mirinda Carfrae, Australians all, dominated the Hawaii Ironman with athleticism and gamesmanship. But it wasn’t just the Australians flooding Hawaii with talent. Canada, with Peter Reid, Lori Bowden and Heather Fuhr delivered championships, and Switzerland’s Natascha Badmann won six times, not to mention Belgium’s Luc Van Lierde who won twice in the late 1990s and Frederick Van Lierde who won this past October.

But the rich history of the Hawaii Ironman goes much deeper. Although the stars of the sport have long generated the most attention, amateur triathletes, competing against all odds, have stirred hearts and minds in ways more dramatic that one could imagine.

Consider the story of a young Brazilian, Carlos Moleda, who moved to the USA at the age of 18, joined the U.S. Navy and became an elite Navy SEAL. In late December 1989, as part of the mission to oust Manuel Noriega from his dictatorship in Panama, Moleda and his squad were caught in a fierce firefight. He was shot in the back and paralyzed. Moleda would regain his identity as an athlete through the emerging wheelchair races that appeared in events like the Boston Marathon and the Hawaii Ironman. As the Big Four helped brand the Hawaii Ironman into a fierce race, Moleda and his eventual antagonist, David Bailey, a motocross champion who had been paralyzed when he crashed going over a jump, would do the same for the physically challenged division at the Hawaii Ironman.

Moleda brought to his training and racing a level of psychological power that he had honed in his Navy SEAL training. In an interview in 2002, he described the moment that he had realized the feverish depth of his tenacity. He described the drown-proofing test that he had to pass to become a SEAL and how it had forced him to dig into a spiritual level of effort: "After they tie your hands behind your back and your feet together, you jump into the deep end of a 50 meter pool,” he said. “First you have to perform an underwater flip so that you’re forced to start out with no momentum; no push off the wall or anything. You start from zero. Then you have to swim the length of the pool underwater, dolphin-style.” Moleda had tried to practice the test on his own over the weekend, but in each attempt he came up well short of finishing, always driven to the surface the need for oxygen. On the day of the actual test, Moleda figured it out. "At the point where I had been forced to come up for air, I could see the wall. Right then, I made the decision I was going to make it." Moleda made it to the wall, surfaced, then screamed in elation. "I knew then what was possible when you reached deep for it," he said. "I think everyone has the capacity for that kind of strength, they just don’t know they have it. They haven’t been put in a situation where they were forced to reach in and find it."

It was 1998 when Moleda arrived to compete at the Hawaii Ironman for the first time, the same year as David Bailey, formerly a professional champion who had decided he would give the Ironman three years of his life, with the unmasked intent of winning the new division. "I figured, three strikes and you’re out," Bailey said. "If I can’t do it in three years, then I’d never be able to do it. But I was confident about it: I figured each of those years I’d win the division. I felt I could beat Carlos for sure. In fact, I thought he’d be easy to beat." Bailey’s prediction seemed spot on. Moleda was one of the last to finish the swim, and Bailey looked to be sailing toward a fairly easy win.

"Hawaii is a mental thing," Moleda said. "There’s a lot of time out there that your mind is going to play with you with negative thoughts, trying to tell you you’ve had enough and should quit. I don’t have those kind of thoughts.”

Indeed, in this 1998 race, Moleda blasted past Bailey and won the first of what would be three epic duels. "I was the better athlete, but Carlos was the better man,” Bailey said. “He completely blew my mind." Once again, a rivalry bent on the mythological was given life through the hardship imposed by the Hawaii Ironman. In 1999, Moleda defended his title with a new record, a 10:55 performance. The second loss shook Bailey, who returned to his home in San Diego and drifted out of shape. "The first thing I did was get fat," he said. "I ate Doritos, I ate donuts. But after a while, I launched into the strictest program I’ve ever been in." The 2000 final matchup between Moleda and Bailey went down in similar fashion as the great Iron War between Allen and Scott. They left the water together, and then spent the 112-mile bike section, using handcycles, to fight brutally for he lead, each trying to break the other man. Bailey raced each mile as if it was his last, and at one point, Moleda flew by him at a pace that seemed otherworldly. Rather than panic, Bailey remained calm and steady, and his emotional patience proved to be the right call. Moleda came back to him, and during the marathon, when the two were charging up a long hill in the beginning of the final stretch of the running leg, Moleda slowed and Bailey pounced. After relentless pressure on one another throughout the hot and humid day, Bailey had hung on to finally win.

The significance of physically challenged athletes competing in what is surely one of the most trying endurance events in existence has also helped brand the Ironman as a place for all-comers. Unlike so many professional sports that hold up a barrier between spectators and elite athletes, the Ironman has effectively smashed down barriers. When race week comes to the Big Island of Hawaii (the race moved from Oahu to the Big Island in 1981), there is little dividing the pros from the age-groupers, besides a press conference for the pros and slightly different start times. The heat, the wind and the distance are the same for all. It seems fitting to end this brief history of the sport with the story of Chrissie Wellington, the British four-time champion that most certainly was, in mind, body and spirit, born for the Hawaii Ironman.

Wellington was a smart, ambitious, academic achiever who was on a service mission in Nepal helping communities get fresh water and plumbing, when she discovered that on high-altitude mountain bike rides, no one, including some very fit men, could keep up with her. She eventually began dabbling in triathlon, with immediate success at the Olympic distance as an amateur. Her talents drew the interest of Australian coach Brett Sutton, who was working to help form a new team of professionals that would train in both Sweden and the Philippines. In a matter of months, under Sutton’s legendary program known for solitude and thorough, focused training within a small squad of dedicated triathletes, Wellington’s enormous talent bloomed rapidly. “She’s like a thoroughbred horse,” Brett Sutton told me in a 2010 interview. “A great thoroughbred doesn’t need that much time to bring all of the speed out.”

It surely didn’t, because within months, Wellington qualified for and competed in the Hawaii Ironman as an unknown name who stunned every other triathlete on the island, save her teammates who had seen her capabilities in training.

That was just the beginning. In each of her four starts at the Hawaii Ironman, Wellington would win, just as she had every Ironman she had entered around the world. But it was in 2011 that one of the most gifted athletes the sport of triathlon has ever seen -- some would say THE most gifted — would be put to an otherworldly test. A few weeks before the start of the race, one in which her coach, 6-time champ Dave Scott, had helped her get into what both felt was the absolute best shape of her career, Wellington crashed during a bike ride in Boulder, falling badly, avoiding any broken bones, but suffering a combination of deep bruising and shredded skin. Her training came to a complete halt as she tried to recover from the severe wounds. As Scott would explain after the race, the energy that her body required to repair the damage had been substantial. Although she flew to Kona with the intention of racing, Scott wasn’t sure if it was even remotely possible. She tried a few workouts,, but an attempt at swimming proved so painful that she broke down crying. Another hospital visit revealed what earlier X-rays had not: a torn pectoral muscle.

Although everyone was aware of the bike accident, Wellington was poker-faced all week, unwilling to fall on any excuses. “I know this sounds cliché and kind of trite, but there are many who have faced more significant physical challenges here than road rash,” she said before the race.

But the extent of the injuries was visible to those who had watched her race before. Particularly during the run, she was plainly fighting against her body, trying to move at the speed she needed to win the race. When her body sent every possible signal for her to slow down and stop, Wellington simply refused to listen. She went on to win her fourth Hawaii Ironman.

It was one of the performances in Hawaii that you see and think: it just can’t get any better than this. There are no more great stories to be told. Yet they just keep coming.

2nd best newsletter in the universe